Extent of jihadist radicalisation in Switzerland almost same as in Germany

Approximately 40% of radicalised jihadists in Switzerland receive welfare benefits, as shown by a ZHAW follow-up study made possible by an extended underlying data base. Furthermore, the proportion of converts is around 20%, which is disproportionately high.

Jihadist radicalisation in Switzerland mainly affects young men from urban agglomerations who have a rather low level of education and poor occupational integration. Some of them are also confronted with social and psychological problems and already had a criminal background before their radicalisation. This has been revealed by updated and extended data, which built on a 2015 ZHAW study entitled “Background to jihadist radicalisation in Switzerland”, headed by Miryam Eser Davolio. The data base consists of a quantitative analysis of information on the background to jihadist radicalisation made available by the Federal Intelligence Service (FIS), as well as interviews with various stakeholders. The data shows that around 40% of the 130 individuals registered as radicalised jihadists are dependent on government support (social assistance, unemployment benefits, disability insurance or refugee assistance). This makes resocialisation, in terms of social integration, a challenge.

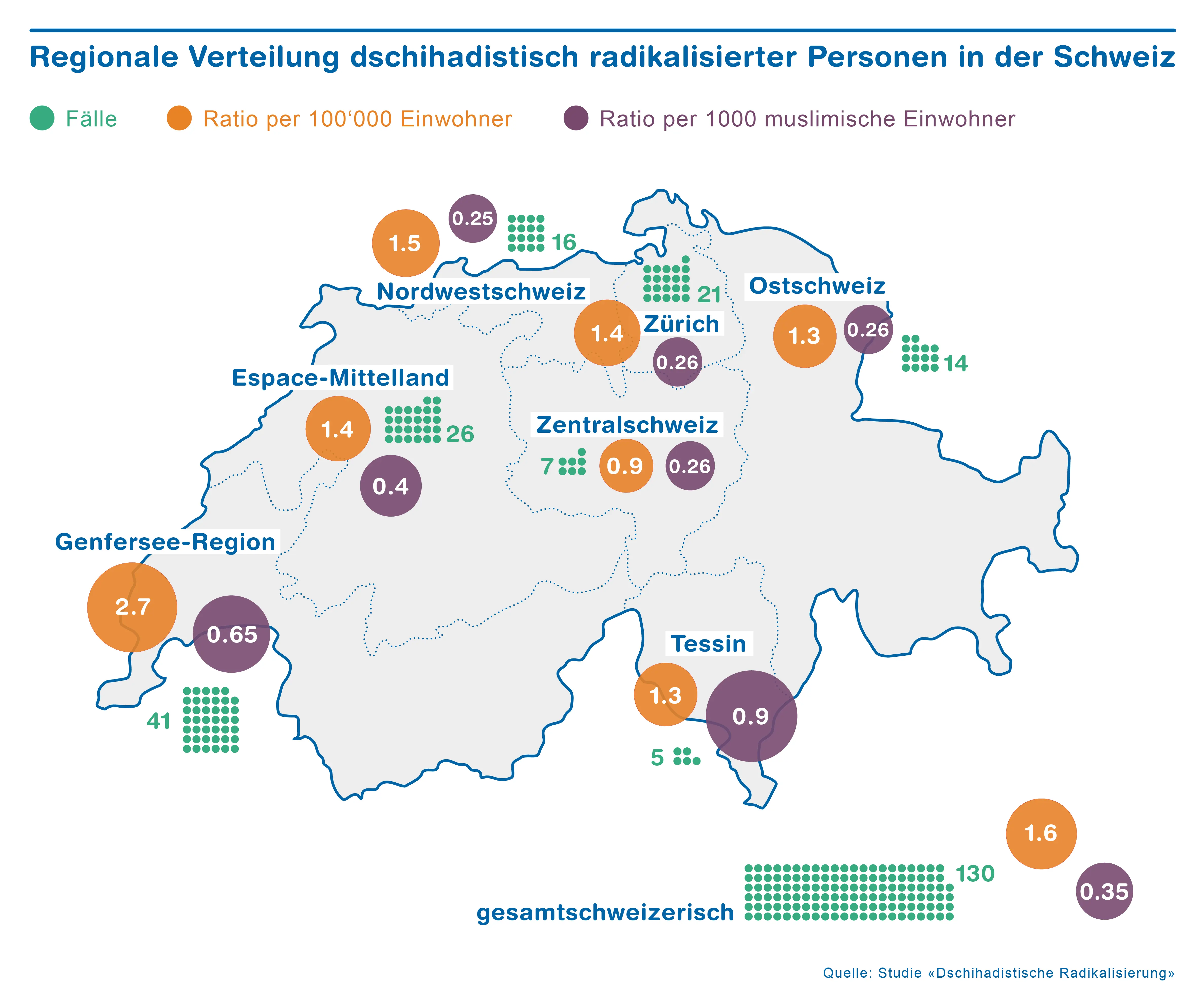

Geneva most severely affected

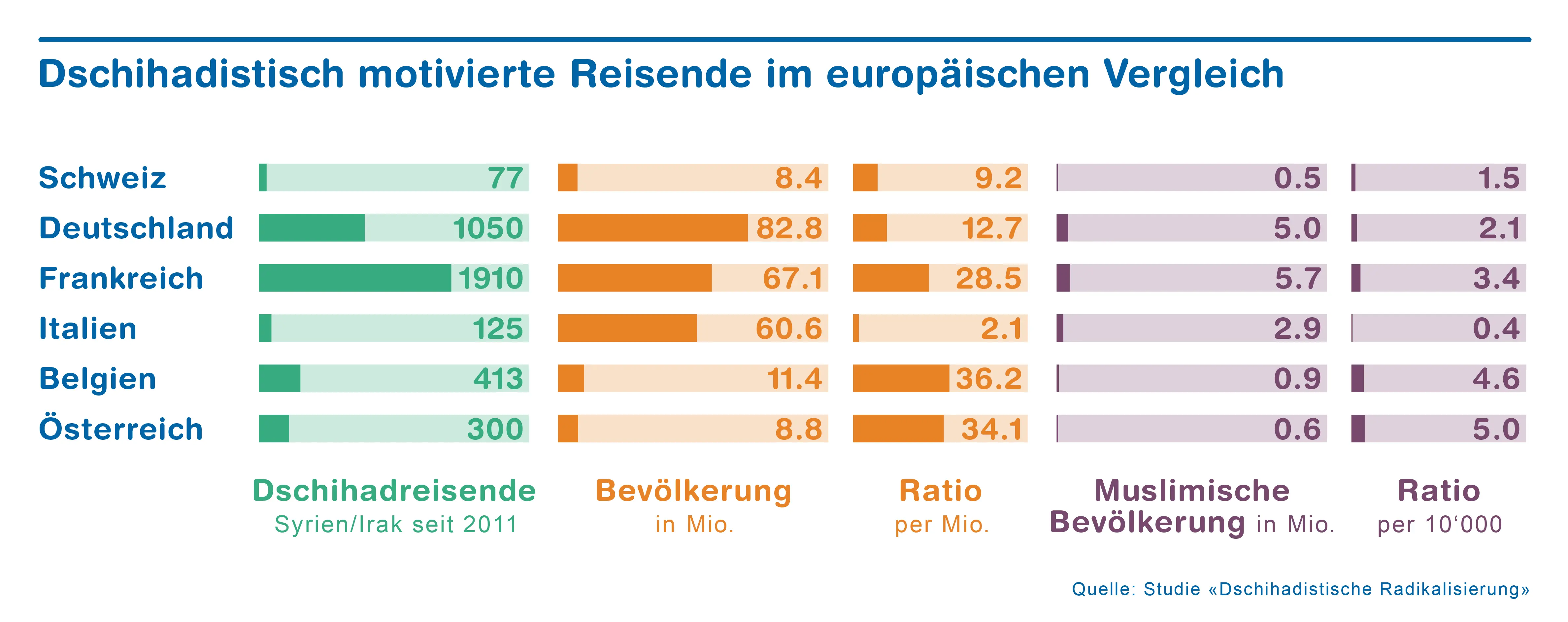

With regard to the geographic distribution of jihadist radicalisation, regional differences can be observed. The Geneva region, for example, is more severely affected than the rest of Switzerland. There are also differences between different European countries. In relation to the country’s total population, Switzerland’s ratio of jihadist travellers is much higher than Italy’s and just slightly lower than Germany’s. However, Switzerland is not as strongly affected by the problem of jihadist radicalisation as are France, Belgium and Austria. The study shows, furthermore, that 20% of jihadist travellers are converts, which is disproportionately high. As they mostly have not shown delinquent behaviour before their radicalisation, Myriam Eser Davolio warns against stereotyping.

The study also found that people affected by jihadist radicalisation are often characterised by a certain alienation from society.

“If we can detect criminal activities or tendencies towards social disintegration at early stages, for example at school or at the workplace, the chances of successful prevention and intervention measures are higher,” explains Miryam Eser Davolio. “We therefore need a multi-perspective approach which takes into account vulnerable individuals’ various deficits and needs,” she adds, and goes on to say that targeted protection measures that eventually protect individuals from propaganda and recruiters are equally important.

“We may conclude from the study that the consumption of certain types of content on the internet does constitute an important supporting condition, but in very few cases is it the sole cause of radicalisation,” says Eser Davolio. Group dynamics and real-world contact with like-minded people are more decisive factors in this respect.

Consequences for the penal system

Miryam Eser Davolio is convinced that the penal system must rise to the challenges posed by radicalised jihadist inmates regarding placement and reinforcement, as well as institutional and individual monitoring.

“Penal institutions need to develop concepts for deliberate handling of existing risks,” she says. Probation officers and social workers, as well as therapists, prison staff and pastoral workers, should be included and should receive focused training so they have sufficient background knowledge and competence to interact with radicalised individuals in an attentive and professional way, according to Eser Davolio. Since it is difficult to implement this comprehensively across the country, the authors of the study suggest developing two to three penal institutions nationwide into special competence centres with a focus on radicalised jihadist inmates. The staff of these competence centres would receive specific training, which is not the case at present, and they would network with one another.

“Extremismus” (extremism) and “Brückenbauer” (bridge building) competence centres have also been developed across Switzerland since 2015, especially in cities and cantons that have been or are affected by jihadist radicalisation. In order to ensure a well-functioning approach nationwide, the authors of the ZHAW study recommend defining minimal requirements on the one hand and further promoting the exchange of experiences between disciplines and competence centres on the other.

Downloads

- Media release «dschihadistische Radikalisierung» DE

(PDF 185,6 KB) - Study «dschihadistische Radikalisierung Schweiz» DE(PDF 692,1 KB)

- Chart «Dschihadismus Schweiz» DE

- Chart«Dschihadismus Europa» DE

- Communiqué de presse «radicalisation djihadiste» FR

(PDF 183,2 KB) - Rapport final «radicalisation djihadiste en Suisse» FR(PDF 741,0 KB)

- Chart «djihadistes Suisse» FR

- Chart «djihadistes Europe» FR

- Research report «jihadist radicalisation» EN(PDF 616,6 KB)

Contact

ZHAW Social Work, Prof. Miryam Eser Davolio, phone 058 934 88 76, email miryam.eserdavolio@zhaw.ch

ZHAW Social Work, Media Relations, Nicole Koch, phone 058 934 88 26, email nicole.koch@zhaw.ch