Victims of compulsory social measures: "I am 17, lonely and abandoned"

Why it would be impossible to come to terms with the dark chapter of compulsory social measures in the canton of Uri without the personal recollections of those affected.

In recent years, the media has often reported on the issue of compulsory social measures. Nevertheless, the opinion was long held in Uri that nobody had ever been institutionalised in the canton. Against this background, we started to investigate the issue of compulsory social measures in the canton of Uri two years ago. The areas covered by our research team from the Institute of Childhood, Youth and Family included admissions to homes and educational work training institutions, the returning of entire families to their home canton and incapacitation. It turned out that the authorities in Uri had institutionalised well in excess of 300 adults and young people during the 20th century, primarily at the nearby Kaltbach correctional labour facility in the neighbouring canton of Schwyz, which existed from 1902 until 1971. Those who failed to follow the strict regime there would spend days or weeks in detention, sometimes even having to do so in the dark if ordered by the warden.

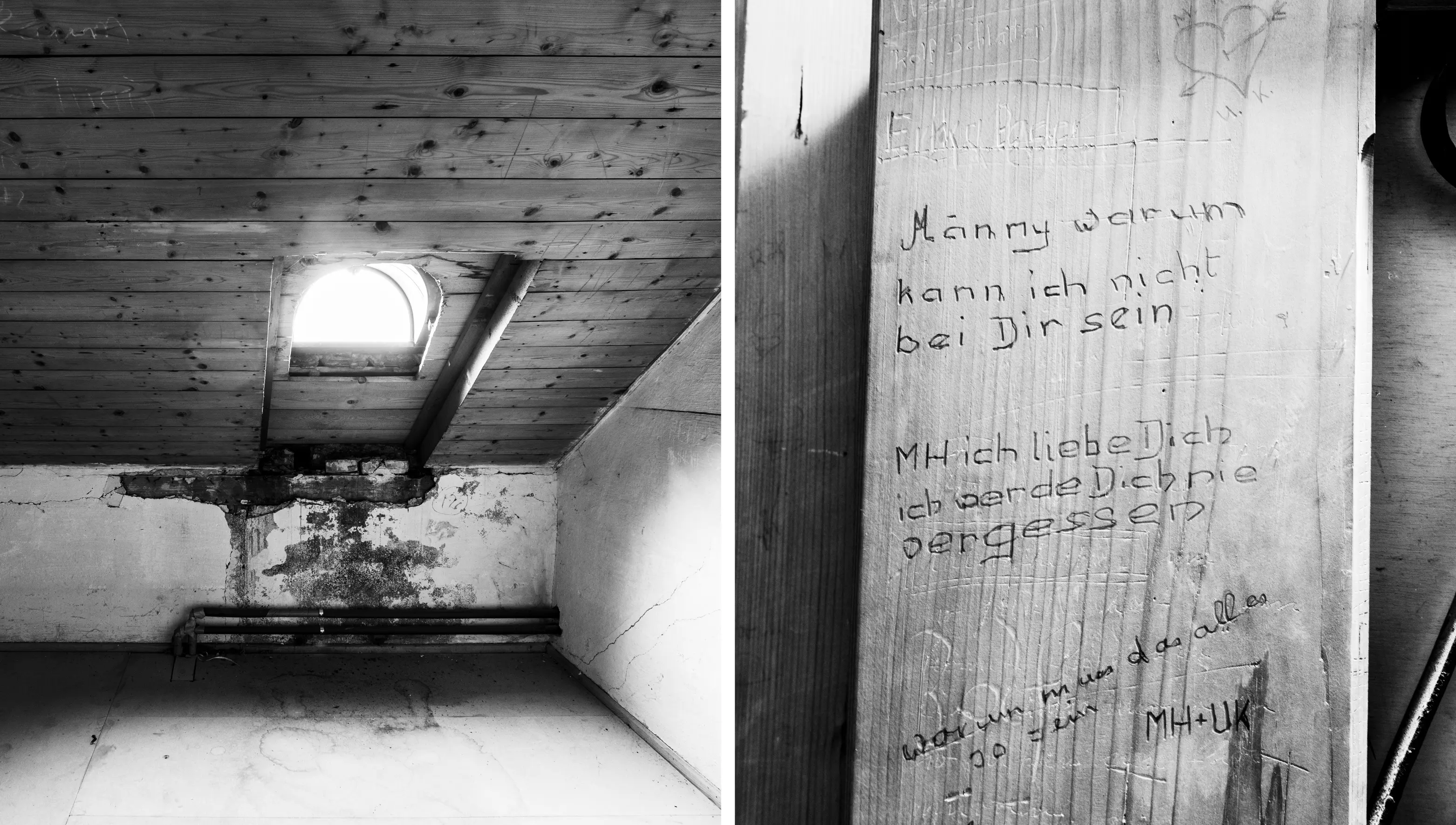

The three cells for the women were located in the attic. In complete isolation, the women would write messages on the walls for those who would follow them into detention. The messages represented a form of resistance: “I am 17, lonely and abandoned. They have left me here because I have a girlfriend. They [the staff] cannot understand any of this because they have no heart for others. They are as cold as marble.” This graffiti still bears witness to everyday life in the institution and the sense of despair felt by the inmates.

Isolated and alone

Every year, the authorities in Uri brought around ten children to the Uri reformatory in Altdorf. The nuns of the Seraphisches Liebeswerk ran the home on a strictly Catholic basis. Everyday life was characterised by constant prayer. Lights out was at 9 p.m. If you were ever caught chatting, you would have to perform a humiliating punishment task, such as going down on your knees in front of all of the other children to wipe up water that the nuns had poured out.

Those affected also report of isolation. At the start of their stay, they were not allowed to visit their parents at all, and even later it would only be for the weekend: “Even phoning home was forbidden. We often felt homesick. Many cried at night in the large dormitory.” Another affected individual paints a similar picture: “You were lonely. The feeling of homesickness in the evening was extremely contagious. There would often be more than ten boys crying in the dormitory.”

A strict daily routine

There is nothing in the files about the experiences described. Instead, they reveal how the members of the authorities viewed those affected. They were often judged to be “work-shy”, “dissolute” or “depraved”. Other archive materials, including the applicable house rules of the time, provide an insight into how the daily routine was organised at the Kaltbach correctional labour facility or the Uri children’s home. The brief reports complied upon the departure of those housed at the institutions in turn give an idea of how the nuns interpreted their educational tasks. They would refer to “secretive”, “dark” and “difficult” characters who they described as “deceitful” and “dishonest”.

These documents fail to provide an impression of how the affected individuals experienced everyday life in Kaltbach or Altdorf. Only the retrospective narratives that they provide or, in the case of Kaltbach, the graffiti they left behind are able to convey this. For our research, we therefore searched for affected individuals in the canton of Uri by means of an appeal communicated via victim counselling services and other channels. Four people came forward and shared their story with us. It is only these descriptions that have made it possible to shine a light on what the compulsory social measures meant for these people in all dimensions.

A deceptive idyll

An example here are the commemorative publications and annual reports on the Uri children’s home. Special events, including excursions, Christmas celebrations and birthday parties were regularly described as highlights of the year. This stands in stark contrast to the recollections of those affected: “There wasn’t much at Christmas, perhaps a few mandarins with candles on the table and a small Christmas tree in the dining room. There were no gifts, however. Christmas wasn’t celebrated. There were no birthday parties either.”

It was said to be important to the nuns to present the appearance of an idyll: “To the outside world, it always had to look hunky dory. […] In the home, we did theatre performances. Important people from the municipality would then come and we simply had to join in, whether we wanted to or not. It was pure staging. Whenever a representative of the authorities paid their obligatory visit, they would only speak with the nuns, not directly to us. […] They never lived up to their responsibility of checking on us.”

Silence forever

The life stories of people in administrative detention are characterised by severe disadvantages and hardship. The situation they faced during their institutionalisation was often hopeless. The method of oral history, in other words interviewing contemporary witnesses, is able to lift a lid on what happened to the affected individuals in the homes and institutions and how they experienced it. The personal stories they share are therefore invaluable for research. Their recollections help to expand the knowledge of compulsory social measures that we have been able to glean from the analysis of written sources.

It took a long time for this to happen in Switzerland. As far back as the 1980s, people who had been subjected to administrative detention demanded a historical reappraisal of what had gone on and that their voices be heard. It was not until the Independent Expert Commission on Administrative Detention was appointed by the Federal Council in 2014 that the calls for as comprehensive a review as possible were met. The topic of welfare and compulsion is also currently being addressed as part of the National Research Programme 76.

However, researchers find themselves confronted with the challenge that the more taboo a topic is, the more difficult it becomes to find affected individuals who are willing to share information. For example, after the Federal Act on Compulsory Social Measures and Placements prior to 1981 came into force in 2017, only 25 people from Uri submitted an application for a solidarity contribution. This represents just a fraction of the people who experienced compulsory social measures. Most of those affected have never shared what happened to them. In some cases, not even their closest family members knew of their fate.